- Home

- Joseph Rodota

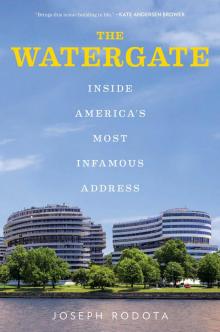

The Watergate

The Watergate Read online

Dedication

To Erik.

For listening with a smile.

And for everything else.

Epigraph

We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.

—WINSTON CHURCHILL

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Part I

1: The Foggy Bottom Project

2: City Within a City

3: Titanic on the Potomac

4: Not Quite Perfect

5: The Maelstrom

Part II

6: A Little Blood

7: The Reagan Renaissance

8: A Nest for High-Flyers

9: Monicaland

10: Done Deal

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

SLAP.

A doorman dropped a copy of the Washington Post at the threshold of a Watergate apartment and continued down the long, curved hallway.

Slap.

He dropped a paper at the next doorstep, and the next, as he made his deliveries through the building.

Slap. Slap. Slap.

Watergate residents—some dressed for work, others still in bathrobes—opened their doors, grabbed their newspapers and stepped back inside their apartments. It was Friday, June 16, 1972. On the front page of the Post, a smiling President Richard Nixon embraced President Luis Echeverría of Mexico at the formal welcoming ceremony on the South Lawn of the White House. The United Nations had launched a new agency to promote international cooperation on the environment, to which the Nixon administration had already committed $100 million. The Soviet news agency Pravda said a thaw in relations with the United States was “both necessary and desirable.” And Raymond Lee “Cadillac” Smith, a legendary figure among Washington’s underworld of pimps, gamblers and hired killers, was finally captured at a Holiday Inn in Kingsport, Tennessee, ending a two-month spree of kidnapping, robbery and murder.

Early risers headed to the Watergate health club to swim in the indoor saltwater pool or use one of the new treadmills, which the club called “mechanical walkers.” Each lap in the pool offered the comfort of routine in an era of unpredictability. Each mile on a treadmill measured progress in a city often frustrated by partisan or bureaucratic gridlock.

The Watergate comprised six buildings spread over ten immaculately landscaped acres: the 213-suite Watergate Hotel; the Watergate Office Building, adjacent to the hotel; a second office building at 600 New Hampshire Avenue, facing the Kennedy Center; and three cooperative apartment buildings, known as Watergate East, Watergate West and Watergate South. (There was no Watergate North.) There was underground parking for twelve hundred cars and a shopping arcade with a number of businesses bearing the Watergate name, including the Watergate Bakery, the Watergate Florist, the Watergate Gallery and the Watergate Beauty Salon. The Watergate had its own bank, a small post office, a Safeway supermarket, one dentist and three psychiatrists. A sophisticated security system, including fourteen cameras in Watergate East alone, recorded the comings and goings of members of Congress, cabinet secretaries, White House aides, journalists, judges and diplomats. Owners of Watergate apartments, from massive penthouses with Potomac River views to modest one-bedrooms overlooking the Howard Johnson Motor Lodge, had something in common: a desire to be close to the center of power in the capital city of the most powerful nation on earth.

Frank Wills, a guard with the Watergate Office Building’s private security firm, wrote in his logbook “all levels” of the building “seemed secured” and ended his shift at 7:00 A.M. He turned in his keys and headed home, passing joggers as they returned to the Watergate from morning runs along the Potomac River or through Rock Creek Park. A small army of housekeepers arrived at the Watergate by bus. It was already in the mid-sixties. By late afternoon, Washington would be flirting with ninety degrees.

Rose Mary Woods stepped into the hall and locked the door to her two-bedroom apartment on the seventh floor of Watergate East. She had worked for Richard Nixon as his personal secretary since 1951, when he moved from the House to the Senate, but she was essentially a member of the family—“the Fifth Nixon,” some said. She headed to the garage for her eight-minute commute to the White House.

At the other end of the Watergate, in a large seventh-floor duplex apartment with both city and river views, Martha Mitchell packed for California. She was still angry with her husband, John, who had resigned as attorney general four months earlier—against her wishes—to become chairman of Nixon’s reelection committee, reprising the role he played during the 1968 campaign. Her unfiltered observations on virtually any topic, from the Vietnam War to the sexual revolution, had made her a national celebrity: Behind only the president and the first lady, Martha Mitchell was the top draw at Republican fund-raisers. Martha, however, was unenthusiastic about this trip to California. She hated to fly. She was overscheduled and exhausted. Besides, Mrs. Nixon was scheduled to attend the fund-raiser in Beverly Hills, which meant Martha would not be the center of attention. “You don’t need me,” she told Fred LaRue, her husband’s top deputy. LaRue pleaded with her. He said his wife, Joyce, wouldn’t go to California unless Martha was on the trip. “I felt sorry for her,” Martha later recalled. “He lived in Washington at the Watergate, and she lived with the kids in Mississippi. She never got to go anyplace.”

Upstairs in her two-story penthouse on the fourteenth floor of Watergate East, Anna Chennault opened the Washington Post and turned to the “Style” section, where she found her name—Mrs. Claire Lee Chennault—on the guest list for last night’s state dinner at the White House, which included four members of Nixon’s cabinet, three U.S. senators and two neighbors at the Watergate: Nixon’s campaign finance chief Maurice Stans and his wife, Kathy, who lived on the tenth floor of Watergate East, and the dashing yachtsman Emil “Bud” Mosbacher, Jr., Nixon’s chief of protocol, and his wife, Patty, who lived in a suite at the Watergate Hotel. Guests dined on scallops and beef with mushrooms. The Nixons served a Schloss Johannisberger Riesling, followed by a claret. After dinner, everyone moved to the East Room and listened to a performance by New Orleans jazz clarinetist Pete Fountain. President Nixon turned to Jack Benny, who had flown in from Los Angeles for the evening, and said it was a tragedy that Benny had left his violin in California.

In his fourth-floor studio apartment, Walter Pforzheimer finished getting ready for work. Since 1956, he curated the CIA’s Historical Intelligence Collection—the spy agency’s in-house library. Pforzheimer owned two apartments at the Watergate: this studio, where he slept and dressed, and a one-bedroom duplex on the seventh floor, where he hosted visitors and displayed his personal collection of espionage literature and artifacts related to spies and spying, including the canceled passport of Mata Hari.

At 8:07 A.M., President Nixon arrived at the Oval Office, just a few steps from the office of Rose Mary Woods. At 8:34, he posed in the Rose Garden for a photo with Vice President Spiro T. Agnew and the entire cabinet, including John Volpe, the secretary of transportation, who lived with his wife, Jennie, in a Watergate East penthouse.

At 9:30, Anna Chennault arrived at the embassy of the Republic of Vietnam, to say goodbye in person to her friend Bùi Diem, on his final day as South Vietnam’s ambassador to the United States.

At 10:17, Nixon adjourned the cabinet meeting and returned to the Oval Office to discuss with a few key aides the progress of welfare reform legislation on Capitol Hill. The day before, nineteen Republican senators had written Nixon urging him to

work more closely with Senator Abraham A. Ribicoff, Democrat of Connecticut, to draft a “humane and decent” welfare reform compromise. Ribicoff and his wife, Ruth, lived in the Watergate, as did two GOP senators who signed the letter: Jacob K. Javits of New York and Edward W. Brooke of Massachusetts.

By 10:00, most of the shops at the Watergate were open. At 11:00, the morning mail was sorted and ready to be picked up at the front desk in each of the three apartment buildings.

At National Airport, just ten minutes and three traffic lights from the Watergate, Martha and John Mitchell boarded a Gulfstream II jet provided to them by Gulf Oil. Martha’s personal secretary, Lea Jablonsky, and the Mitchells’ eleven-year-old daughter, Marty, joined them on the flight to California. Marty looked forward to visiting Disneyland. Martha looked forward to getting a few days’ rest at the beach.

At noon, following a quick stop at the South Korean embassy to meet with Ambassador Kim Dong Jo, Anna Chennault met Ray Cline for lunch. Their friendship went back decades to her days as a reporter in China, before the Communists seized power. Cline, the former CIA station chief in Taipei, now directed intelligence gathering for the State Department.

Back at the Watergate, women gathered to swim, sunbathe and gossip at one of the three outdoor swimming pools. Each “regular” had her favorite spot. “If it only had a tennis court and a movie theatre,” said Mrs. Herbert Saltzman, who lived next door to Senator and Mrs. Javits in Watergate West, “I don’t think I’d ever have occasion to leave the place.”

The Mitchells and their entourage arrived in Los Angeles and were whisked off to the Beverly Hills Hotel. It had been a long flight. After a room-service dinner, John retired early and Martha stayed up and had a few drinks.

Four men, using assumed names, arrived at National Airport and took a taxi to the Watergate Hotel. They checked into suites 214 and 314. At 8:30 P.M., they dined on lobster tails at the hotel restaurant.

At 10:50, a man signed the logbook in the lobby of the Watergate Office Building and took the elevator to the eighth floor, where the Federal Reserve kept an office. He taped open the stairwell locks on the eighth floor before continuing down to the sixth floor, taping its door as well as the doors on the B-2 and B-3 levels, and those leading to the underground garage.

On the sixth floor of the Watergate Office Building, in the offices of the Democratic National Committee, Bruce Givner, a twenty-one-year-old summer intern from UCLA, was making use of the committee’s free long-distance telephone. He called friends and family back home in Lorain, Ohio, pausing only to step onto the balcony and relieve himself in one of the potted plants. He was observed by a man stationed in Room 723 of the Howard Johnson Motor Lodge, across the street, who passed word to the men in Room 314 of the Watergate Hotel that the DNC suite was still occupied.

At 11:51, Frank Wills returned to the Watergate Office Building to begin his midnight to 8:00 A.M. shift. He made his rounds and discovered tape on the door locks at levels B-2 and B-3. He removed the tape, returned to his desk in the lobby and documented his discovery in his logbook. He called the answering service for GSS, the private security firm for which he worked, and left a message for his supervisor to call him.

Shortly after one in the morning, on Saturday, June 17, 1972, five men took the elevator from the second and third floors of the Watergate Hotel down to the underground garage and made their way to the Watergate Office Building.

Within a few hours, the Watergate—and the nation—would never be the same.

Part I

Chapter One: The Foggy Bottom Project

Recognizing the outstanding possibilities of the site on the River; its strategic location to the Center of the City; the close proximity of significant developments (both actual and planned—The State Department, Lincoln Memorial, National Cultural Center . . . ); the architects approached the problem by providing a “Garden City within a City” where people could live, work, shop, and play, with cultural opportunities within walking distance.

“The Watergate Development,” February 28, 1962

IN 1946, THE WASHINGTON GAS LIGHT COMPANY BEGAN switching its customers in Maryland, Virginia and the District of Columbia to “natural” gas, which meant the West Station Works, where coal was converted to “mixed” gas, was no longer needed. The land beneath the plant, a six-and-a-half-acre parcel bordered by the Potomac River and Virginia and New Hampshire Avenues, was now for sale at $3 million. There was some flexibility in price—the company was “open to offers,” subject to approval by the board of directors of the Washington Gas Light Company—but the property was only available in its entirety. Any “piecemeal” offers, the Washington Post reported, would be rejected.

John Nolen, Jr., the staff director of the National Capital Planning Commission, the federal agency formed in 1924 to oversee planning within the District of Columbia on behalf of the federal government, said he would support residential or other uses for the gas company site—as permitted under existing zoning—provided they were “harmonious” with the major federal buildings planned nearby, including the massive new State Department headquarters. The gas company printed up a brochure with illustrations of eight- and five-story apartment buildings that could potentially be constructed on the property. According to the brochure, a buyer would find support among city planners for closing streets and merging the lots spanning F, G, H, 26th and 27th Streets—on the same grid originally laid out by Charles L’Enfant—into a single buildable site, “thus adding materially to the value of the property.” The gas company, however, retained an adjacent parcel where two massive gas storage tanks were located. “It could be the best residential area in town,” observed the District of Columbia’s top planning bureaucrat, “were it not for those tanks.”

One week after Harry S. Truman surprised Thomas E. Dewey, the Chicago Daily Tribune and the nation by winning the 1948 presidential election, a crowd of two hundred “real estate men” gathered in the East Room of the Mayflower Hotel, a thirteen-minute walk from the White House. Local auctioneer Ralph Weschler, hired by the gas company to sell the property, called it the District’s “most strategic” development opportunity, by virtue of its location overlooking the Potomac River, within a two-mile radius of the city’s most important office buildings. Hotelier Conrad Hilton read the auction prospectus carefully, but decided not to bid. He could not figure out what to do with the oddly shaped site. Roy S. Thurman, a local developer with an uneven track record, was undeterred by the nearby gas storage tanks. He thought the waterfront parcel would make a good spot for apartments and a shopping center and opened the bidding at $750,000. Stanford Abel, treasurer of a local engineering firm, who told a reporter he had “nothing special” in mind for the land, raised his paddle. The two men bid against each other until Abel dropped out, leaving Thurman the high bidder at $935,000. Marcy L. Sperry, president of the gas company, promptly declared the bid unacceptable. Weschler then offered each of the six lots individually. He looked around the room, but was met only with stares. There were no bidders. Within a few minutes, the auction was over.

When the Washington Gas Light Company finally announced plans to dismantle its unsightly gas storage tanks, George Preston Marshall, owner of the Washington Redskins football team, decided to pounce. With John W. Harris, developer of the Statler Hotel in New York, Marshall formed a syndicate and purchased an option to develop most of the gas company land in Foggy Bottom, about ten acres. In September 1953, they revealed plans for Potomac Plaza Center, a “high character” project, including a thousand-room hotel, a two-thousand-car garage, six office buildings, two apartment buildings, a shopping center, an ice rink and a yachting marina, at a total cost of $75 million. Time magazine called the proposed development “Rockefeller Center–like.” The firm of Harrison & Abramovitz, architects of Rockefeller Center, had designed the project. In the summer of 1955, Harris brought in a new investor, American Securities Corp. of New York, which agreed to supply working capital for the project an

d help raise up to $100 million in financing for the Potomac Plaza Center project. American Securities made a “substantial cash deposit” with the Washington Gas Light Company, extending the option on the land another five years.

LA SOCIETÀ GENERALE IMMOBILIARE DI LAVORI DI UTILITÀ pubblica ed agricola (in English, “General Building Society of Works of Public and Agricultural Utility”) was the largest real estate development and construction firm in Italy. To the company’s employees, it was known as Immobiliare. In the media, the firm was usually identified as either Società Generale Immobiliare or by its initials, SGI. The company was as old as Italy itself: Founded in the northern city of Turin in 1862, SGI moved its headquarters to Rome in 1870, just as that city became the capital of the Kingdom of Italy. Over the decades, SGI cleared slums, enlarged plazas throughout Rome, and created large suburban developments outside the city. These subdivisions had all the amenities, from roads and utilities to churches and soccer fields. For the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome, SGI built the Olympic Village. In partnership with Hilton Hotels, the company built the Cavalieri Hilton on a hilltop overlooking Vatican City, beating back protestors who wanted the site preserved as a public park. Eugenio Gualdi, an engineer and former president of the Lazio soccer organization, was managing director and chairman of the board. But the key figure in transforming SGI into a “construction titan,” according to Time magazine, was Aldo Samaritani.

Samaritani, trained as a banker, joined SGI in his late twenties and was now vice director of the firm, second only to Gualdi, with the understanding he would take control of SGI when Gualdi retired. With his neatly trimmed mustache and slicked-back hair, Samaritani appeared easygoing and modest, but he was shrewd, competitive and disciplined. Colleagues called him “a human computer” for his ability to juggle financial and other details for every SGI project. He worked twelve-hour days, which left him little time for his seven children and eleven grandchildren. He looked forward to retirement. “Many of my colleagues fear the vacuum that will be created in their lives when they stop working actively,” he told a reporter. “But I will have more than enough to do—seeing hundreds of movies I have missed, reading hundreds of books that I have left unread, listening to phonograph records that others have heard.”

The Watergate

The Watergate